[Edit > A new version of Platform Design Toolkit is is coming up. See here for the latest release of the Draft Open For Comments of the PDT 2.0 http://platformdesigntoolkit.com/]

(Italian translation of the post can be found here)

In recent months, lots of my research has been devoted to develop and learn new visual analytical tools suited to different activities and phases of a business lifetime.

The most important of these tools, as you will probably know if you are a regular reader, is the Platform Design Canvas that I recently launched. This Platform Design Canvas (or PDCanvas) is a tool for product, service and venture design created for the social era. I created the Canvas in July and presented it for the first time during the Barcelona Design Thinking Week at the Elisava Design School. The Canvas and the related presentation were very favourably received by the community and I’ve reflected on the Canvas throughout all summer. I used the canvas a lot with some of my key clients and I also had the chance to confront with people that used the canvas on their own, within their business contexts by themselves.

Finally, just a few days ago, I had the chance to present the tool at Frontiers Of Interaction 2013, one of the best European international conferences on design and innovation. I got an amazing chance to test the Canvas since nearly sixty attendees showed up in a mega-workshop with nine working groups that used the tool both on fictional and real business scenarios, and helped me to collect an amazing number insights and feedbacks. Here follows a video shoot at #FOI13 in which I explain a bit more about the Canvas:

All these Platform Design Canvas early adopters helped me to focus on some of the Canvas limitations (in terms of clarity and process) and to develop a more a clearer best practice for self managed adoption of it.

A Toolkit, more than a single Canvas

As I recently anticipated in this piece and the related presentation I think that, in parallel to the tuning of the Canvas itself, there’s a strong need to integrate it with a set of other ancillary tools.

Some of the tools in question – the basic core of a strategic Platform Design Toolkit useful to those who want to design products in line with our brand new today – are once again borrowed from the world of Design Thinking. I think in these days we need Design Thinking community of practice that looks for more inclusion towards people not having a actual Design background. That’s why I’m working on toolkits and Canvases: those instruments are powerful when it comes to inclusion.

Coming back to the toolkit, the first addition I’m doing to it will be a derivation and specialization, of a rather classical and well known design thinking tool, i.e. a motivations matrix. Motivation matrixes are often used by Service Designer all over the world to identify and investigate the motivations behind each single entity that interacts within a service context.

In any context where it has to do with a number of internal and external actors, it’s crucial to understand the role their motivations play while they participate in value co-creation. The analysis of the value creation process is a critical step for understanding the platform: motivations are inextricably linked with that process and, therefore, are essential to understand.

Peers and Stakeholders

So, while applying the Platform Design Canvas in some of my client’s contexts I’ve found important – before setting up the actual Canvas – to analyze the motivations of the two main interest groups behind the platform itself: those that I call Stakeholders and Peers.

When we analyze ecosystems and platforms in fact, the first distinctions we need to make, with regard to the different entities involved, it is exactly this.

Stakeholders are primarily those entities responsible for cooperatively grow, maintain and adapt the platform within time. Stakeholders could also include those who, having adjacent but non-overlapping missions, could affect the same platform success through their actions. From my experience, I can say that it is common that a platform has one main stakeholder (which, in most cases, is the platform owner). Less frequently, but this is particularly true with open ones, platforms could have several other stakeholders, that could be more or less marginal to the context. However, especially in the early stages of the transformation from a linear business to a multi-sided one, or in general in the early stages, the platform often has only one stakeholder-owner, that basically is the creator of the platform.

The Peer Segments are the different groups of users involved in the platform with different but potentially overlapped roles. Some roles are typically clearly identifiable from scratch: usually, each platform has one or more peer segments playing a producer role (for example companies and individual developers creating apps on a mobile marketplace) and one or more peer segments playing the consumer role. Often, especially in mature platforms, there are other potential roles coming up: some that often emerge are that of the broker–facilitator or that of curator-distributor (think of a blogger reviewing WordPress templates). Often, these ancillary roles are linked to the facilitation of transactions that eventually make the platform valuable.

A process to identify Platform Stakeholders and Peer Segments

The simple, linear process to identify the entities (both stakeholders and peer segments) involved in the platform that I use most often, is to generate an initial map through a brainstorming-metaplan phase (where each participant in the strategic design session, that should be cooperative, indicates what she thinks are the entities involved). The entities enumerated should be then prioritized, by means distributing them across a four quadrant schema, according to the approach described in the aforementioned Stakeholder Mapping that you can find on the Go Gamestorm portal: I usually map entities according to potential impact for platform success, and according to the level of interest they have, or may have, in using the platform. Note that, while the process as it’s described on the Go Gamestorm portal dubs everyone as “stakeholder”, we use this term to identify just one of the classes of entities, the platform stakeholders exactly, and dub the others as peer segments.

Prioritization of stakeholders and peer segments is crucial because, being the meta-plan a brainstorming technique, we inevitably tend to produce a very large set of entities in that phase, where even marginal players are often mentioned. Unfortunately to carry out this type of analysis with more than six or seven entities is incredibly complex (the matrix grows with the square law): for this purpose is therefore important to prioritize them and pick the priority ones.

Once you are sure to have identified a reasonable set of actors to analyze, we can proceed to place them within the motivations matrix.

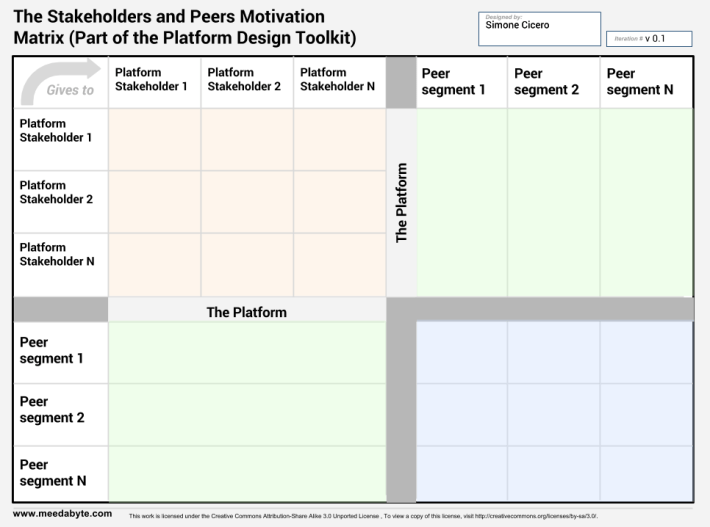

The biggest difference with respect to classical use of the motivations matrix, is the clear separation between stakeholders and peer segments that we put in place that you can see in the figure below, picturing the Platform Motivations Matrix.

The approach that I recommend, is to start by addressing the analysis of the motivations that are internal to the platform – between platform stakeholders – and then going through a second phase regarding the external ones, those that arise between the peer segments: in that phase considering the platform as a single item. The matrix template is designed for this.

The motivations are then mapped very simply: by using the “gives to” metaphor every cell in the matrix will represent what the entity in that line, provides the one in the column. The diagonal instead, will have to gather the intrinsic motivations and interests that each entity has in participating in the platform. A clear example of a traditional, service design related, motivation matrix can be seen here at Service Design Tools.

This first phase of analysis, then provides your team with a clear understanding of the whys that you can then use as a foundation for the actual Canvas examination.

The Platform The Design Canvas version 0.2

In addition to the release of the Platform Motivations Matrix, I’m also releasing a new iteration of the canvas, version 0.2. The changes are not many but they are quite important for a better understanding: the canvas is now clearer and more self-standing.

The first, a tiny change in the canvas is the inversion between Value Extractions and Value Exchanges. This small change, however, allows us to look to the canvas with much more clarity and to identify two main areas.

In effect, due to this modification, the left side of the Canvas is now primarily concerned with what I call Social & Community Dynamics: everything related to creating socially and communal shared value.

As you can easily see, in this part of the canvas you’ll find:

- KEY STAKEHOLDERS – The key stakeholders of the platform (as depicted above)

- KEY COMMUNITY SUPPORT SERVICES – The services that these stakeholders create to support the development of the Community of peer segments

- PLATFORM KEY COMPONENTS – The tangible key components of the platform. These are the basic components such as common interfaces, standards that underpin communication, or things more traditionally considered as components, like infrastructures or support products (such as an IDE, when it comes to a software development platform)

- VALUE EXTRACTIONS – The value that the owner (or, in some cases, key stakeholders) extract from the platform, in exchange of the just mentioned services and components that they provide

In the righter part, on the other hand, we can find the dynamics related to the peer to peer interactions (between peers coming from the different segments) and therefore exchanged value:

- PEER SEGMENTS – The Peer Segments (as described above, all recognizable groups of users such as producers, consumers and others)

- KEY TRANSACTIONS – The recurring Transactions between the different peer segments that characterize the peer to peer platform (often tangible expressions of the relationships among the peer segments). Typical transactions can be the purchase or use of an asset or another example may be the review or the recommendation. It’s a good practice, when a real transaction is not yet emerged, to use this part of the canvas to track the relationship and the availability of a specific channel. Channels are fundamental to give rise to new forms of potential transactions.

- CHANNELS – In fact, I think this is the most important part of the Canvas: the channels are the transactions enablers and, consequently, are the vehicles through which the value is exchanged between the peers. Ideally, each transaction (or potential) must have a dedicated channel to reduce friction.

- VALUE EXCHANGES – This is another key component of the canvas. Here we map the type of value that is exchanged during transactions. Typically each transaction corresponds to a channel and to a value exchange. As an example let’s think of recommendations in p2p marketplaces (common form of platform): in this case the channel is typically the very same marketplace portal and the form of value traded is reputation (through a textual, or score review).

The last part that remains is the core and central part of the Canvas: this has also been subject to review in this passage from 0.1 to 0.2. In particular, I noticed that the term Value Creation wasn’t clear and could be partially overlapped with the other aspects already on the canvas related to value flows and value lifetime.

That’s why I decided to come back to the definition of Value Proposition (as in the original Business Model Canvas). This part of the canvas is likely to collect most of the aspects that, if we’re lucky, we’ve already identified in the diagonal of the motivation matrix. In fact, the intrinsic motivations of peers are a good starting point to understand the value that they get from being part of the platform. This change was mostly introduced after someone from the community noted that the canvas was lacking a part where to track WHAT value was created, rather than HOW.

The following figures, show the canvas and the highlight of the two different zones (Social & Community Dynamics for shared value and P2P Dynamics for exchanged value):

A practical step by step guide to using the Platform Design Canvas

Latest experiences using the Platform Design Canvas led me to consolidate a step by step procedure (which surely can be tuned, according to your situation), that can serve as a starting point for platform analysis.

One thing that is worth mentioning, I usually first complete the Platform Motivations Matrix before going through the actual Canvas.

The sequence that I usually follow in applying the canvas is as follows:

Step 1 – Identify the Value Proposition: as mentioned before, much of the value proposition should be clarified before starting the analysis on the canvas. As always, the value proposition in about solving people’s problems and is therefore tied with the intrinsic motivations of peers and stakeholders to participate. In a marketplace, for example, the value proposition is often related to the ability to monetize intellectual assets, skills or resources.

Step 2 – Enumerate Platform Stakeholders: stakeholders analysis should be clear at this point (see above, and use the matrix).

Step 3 – Enumerate Peer Segments: in the same way, at this point you should have a clear understanding on how to identify peer segments (see above, and use the matrix).

Note that, we cannot exclude that further analysis (during platform lifetime) reveal additional peer segments or new stakeholders. The platform designer should continuously look for new actors and make them part of the value creation process that the platform looks to enable.

Step 4 – Identify Key Transactions: the first three steps will provide a basis for the identification of transactions between peer segments (as described above).

Step 5 – Identify existing and required Channels: this is a crucial step of the analysis, you need to identify if existing channels are sufficient to model the existing transactions or if new channels have to be created to specifically facilitate un-channeled transactions and liberate potential value exchanges.

Step 6 – Analyze Value Exchanges: the value exchanged must be the main object of the analysis since, after all, this is exactly the main aspect differentiating platforms from linear products. Platforms exist to facilitate value exchanges between peer segments . This is exactly what makes a platform more resilient respect to linear products since you allow users to create complex bonds and relations and this ends up securing the future of your product, service or context. When you map the exchange of value it’s always good to keep track of which channel is used to make this exchange possible (typically tied 1 to 1 with a transaction). What is interesting to analyze, beyond the transaction the value exchange refers, is the form in which the value is exchanged. We could have monetary exchanges as well as ones involving other currency types and value forms. That aspect should be taken into account when you fill out the canvas (take note of the form of value exchanged, it helps make it tangible).

Step 7 – Identify Key Platform Components: at this point you should be able to identify the key components of the platform. The difficult part may be the identification of additional components that, within time, should be developed. Sometimes, a particular component of the platform can be an agreement or a standard that facilitates the value exchange (paired with the appropriate channel) improving the health of the platform. In other cases, components may be simple tools (e.g. software development IDEs in software development platforms) or physical spaces and infrastructures.

Step 8 – Identify Key Community Support Services: once you modeled peer segments and other actors that create value through the platform, you will also understand that this community needs a number of support services to work at its best. Typically, these services are needed to facilitate the emergence of quality, enable discussion and confrontation on future changes and can generate powerful innovation dynamics. These dynamics, at the end of the day, represent the real soul of the community and of the platform itself. Services could also be needed to ensure the quality of relations and exchanges. Typical examples of services could be, organizing conferences and meetups, free complementary services for members: think to identity verification services or, for example, the professional photography service that AirBnb gives for free to users.

Step 9 – Analyze Value Extractions: at the conclusion of this detailed analysis, you will have a very clear understanding of actors and use cases of the platform and you’ll know everything about the services needed to ensure that value is generated and exchanged. It is therefore possible to have a precise understanding of what and how value is created and in what ways and contexts it can be fairly extracted by the platform owners, in exchange of the services and components that the they provide. Usual forms of value extractions could be commercial fees on sales transactions, campaigns to crowdsource innovations and ideas, or just user attention such in ad supported platforms like Facebook.

A Platform Design Toolkit in the making

The Platform Design Tookit is de facto out as a draft, composed by two tools, and waiting for your feedbacks: the tools are live for comment here and here. Access it as a link bundle here.

Over the next days and weeks I’ll publish undisclosed case studies and further analysis of the Platform Design Toolkit, especially in light of feedback I had during Frontiers of Interaction mega-workshop. For now I hope that this guide will give you detailed inspiration about how to use the Toolkit in your own innovation and business context and hopefully give me feedbacks in re-calibrating the tool.

Thanks in advance.

It follows a power point presentation of the new update:

Great work Simo! Is it possible to digitalize this into a CRM like Podio?

Pingback: How to Frame the Sharing Economy Narrative (and Move On) | Meedabyte

Pingback: Una clase con Albert Cañigueral | Startup Liquid

Pingback: The Platform Design Toolkit is in the Making | ...

Pingback: The Platform Design Toolkit is in the Making | Fred Zimny's Serve4impact

Pingback: Why choose to be Open Source in the Hardware Industry | Open Electronics

Pingback: Welcome to Post Capitalism (plus 5 layers of Corporate Transformation) | Meedabyte

Pingback: The Platform Design Toolkit is in the Making | ...

Pingback: Whatever it Takes to Change the World: Back From OuiShare Fest 2014 | Meedabyte

Pingback: Open Platform Design Flowchart vs 0.2 released | blog LZ

Pingback: Annabel Lemkes – Week 41 – Inspiring conversation with ShareNL | VU Minor Entrepreneurship

Pingback: Umbrella Design Toolkit - mastering mega-events

Pingback: Venture Capital and Marketplace Startups | The Rebel VC

Reblogged this on Yves Zieba and commented:

Great for anyone aiming at building a platform business

Pingback: Introducing The Platform Design Toolkit 2.0 | Meedabyte

Really inspiring work! That will be the basis for the OBM efforts to build our platform too, thanks a lot!!!

Don’t forget to check the new version 😉 https://meedabyte.com/2015/11/06/platform-design-toolkit-2-0-open-for-comments/

Thanks for sharing this toolkit! It´s very helpfull. For me it´s not clear how o use the motivation matrix. Do you have an example to share with us?

Ciao Ana, please look into http://www.platformdesigntoolkit.com – there’s a user guide, blog, newsletter….